Below are my notes from the book Good Code, Bad Code. They are copied directly from the book and cover most of the main ideas. In my opinion, they may be sufficient if you don’t plan to read the book itself. However, the book provides more in-depth explanations and plenty of code examples.

Chapter 1 (Code Quality)

Notes

- There are four high-level goals that I aim to achieve when writing code:

- It should work

- It should keep working

- It should be adaptable to changing requirements

- It should not reinvent the wheel

- The six pillars of code quality are:

- Make code readable

- Avoid surprises

- Make code hard to misuse

- Make code modular

- Make code reusable and generalizable

- Make code testable and test it properly

- An engineer using our code will use cues such as names, data types, and common conventions to build a mental model about what they expect our code to take as input, what it will do, and what it will return. If our code does something outside of this mental model, then it can very often lead to bugs creeping into a piece of software.

- Reusability means that something can be used to solve the same problem but in multiple scenarios. Generalizability means something can be used to solve multiple conceptually similar problems that are subtly different.

- To ensure that the code we write is testable, it’s good to continually ask ourselves “how will we test this?” as we are writing the code. Therefore, testing should not be considered as an afterthought: it’s an integral and fundamental part of writing code at all stages.

- Just coding the first thing that comes into our heads, without considering the quality of the code, will likely save us some time initially. But we will quickly end up with a fragile, complicated code base, which becomes increasingly hard to understand or reason about. Adding new features, or fixing bugs will become increasingly difficult and slow as we have to deal with breakages and re-engineering things. (“less haste, more speed”)

Summary

- To create good software, we need to write high-quality code.

- Before code becomes software running in the wild, it usually has to pass several stages of checks and tests (sometimes manual, sometimes automatic).

- These checks help prevent buggy and broken functionality reaching users, or business critical systems.

- It’s good to consider testing at every stage of writing code; it shouldn’t be considered as an afterthought.

- It might seem like writing high-quality code slows us down initially, but it often speeds up development times in the mid to long term.

Chapter 2 (layers of abstraction)

Notes

If we do a good job of recursively breaking a problem down into subproblems and creating layers of abstraction, then no individual piece of code will ever seem particularly complicated, because it will be dealing with just a few easily comprehended concepts at a time. This should be our aim when solving a problem as a software engineer: even if the problem is incredibly complicated we can tame it by identifying the subproblems and creating the correct layers of abstraction.

Building clean and distinct layers of abstraction goes a long way to achieving four of the pillars of code quality

- Readability: Creating clean and distinct layers of abstraction means that engineers only need to deal with one or two layers, and a few concepts at a time. This greatly increases the readability of code.

- Modularity: When layers of abstraction cleanly divide the solutions to subproblems and ensure that no implementation details are leaked between them, then it becomes very easy to swap the implementations within a layer without affecting other layers or parts of the code.

- Reusability and Generalizability: If the solution to a subproblem is presented as a clean layer of abstraction, then it’s easy to re-use just the solution to that subproblem. And if problems are broken down into suitably abstract subproblems, then it’s likely that the solutions will generalize to be useful in multiple different scenarios. -Testability: If the code is split cleanly into layers of abstraction, then it becomes a lot easier to fully test the solution to each subproblem.

It’s often useful to think of the code we write as exposing a mini API that other pieces of code can use. Engineers often do this, and you will likely hear them talking of classes, interfaces, and functions as “exposing an API”.

Functions

- A good strategy to try and ensure that functions can be translated into sentences that make sense, is to limit a single function to either of the following:

- performing one single task

- composing more complex behavior by just calling other well-named functions

Classes

- Engineers often debate what the ideal size for a single class is, and many theories and rules of thumb have been put forward such as those that follow:

- Number of lines: You will sometimes hear guidance such as “a class shouldn’t be longer than 300 lines of code.”

- This rule of thumb does not imply that a class that is 300 lines or fewer is an appropriate size. It serves only as a warning that something might be wrong

- Cohesiveness: This is a gauge of how well the things inside a class “belong” together, with the idea being that a good class is one that is highly cohesive. A couple of examples cohesiveness are:

- Sequential cohesiveness: This occurs when the output of one thing is needed as an input to another thing.

- Functional cohesiveness: This occurs when a group of things all contribute towards achieving a single task.

- Separation of concerns: This is a design principle that advocates that systems should be separated into individual components that each deal with a distinct problem (or concern).

- Number of lines: You will sometimes hear guidance such as “a class shouldn’t be longer than 300 lines of code.”

- It’s important to think about whether a class is getting too big both when modifying existing code, as well as when writing completely new code.

- Rules of thumb like “a class should only be concerned with one thing” or “a class should be cohesive” exist to try and guide engineers to create higher-quality code. But we still need to think carefully about what we’re fundamentally trying to achieve. With regard to layers of code and creating classes, four of the pillars that were defined in chapter one capture what we should be trying to achieve:

- Readability: The greater the number of different concepts that we bundle together into a single class, the less readable that class is going to be.

- Modularity: Using classes and interfaces is one of the best ways to make code modular. If the solution to a subproblem is self-contained inside its own class and other classes only interact with it via a few well thought out public functions, then it will be easy to swap out that implementation with another one should we need to.

- Reusability and Generalizability: If solving a problem requires solving two subproblems, then there’s a reasonable chance that someone else might need to solve one of those subproblems as well in the future. If we bundle the solution to both subproblems together into one class, then it reduces the chance that someone else will be able to reuse one of them.

- Testability: If logic is broken into classes, then it becomes a lot easier to properly test each piece of it.

- Large classes that do too many things are all too common in a lot of codebases, this often leads to a reduction in code quality. It’s good to think carefully when designing a class hierarchy about whether it meets the pillars of code quality that were just discussed. Classes can often grow organically over time to become too big, so it helps to think about these pillars when modifying existing classes, as well as when authoring new ones. Breaking code down into appropriately sized classes is one of the most effective tools for ensuring we have good layers of abstraction, so it’s worth spending time and thought on getting it right.

Interfaces

- If we have more than one implementation for a given abstract layer, or if we think that we will be adding more in the future, then it’s usually a good idea to define an interface.

- Interfaces are an extremely useful tool for creating code that provides clean layers of abstraction. Whenever we need to switch between two or more different concrete implementations for a given subproblem, it’s usually best to define an interface to represent the layer of abstraction. This will make our code more modular, and much easier to reconfigure.

- Despite the benefits, there are some overheads associated with breaking code into distinct layers, such as the following:

- More lines of code, due to all the boilerplate required to define a class, or import dependencies into a new file.

- The effort required to switch between files or classes when following a chain of logic.

- If we end up hiding a layer behind an interface, then it requires more effort to figure out which implementation is used in which scenarios. This can make understanding logic, or debugging more difficult.

- These costs are generally quite low compared with all the benefits of having code that is split into distinct layers, but it’s worth remembering that there’s no point in splitting code just for the sake of it. There can come a point where the costs outweigh the benefits, so it’s good to apply common sense.

Summary

- Breaking code into clean and distinct layers of abstraction makes it more readable, modular, reusable, generalizable, and testable.

- We can use functions, classes, and interfaces (as well as other language-specific features) to break our code into layers of abstraction.

- Deciding how to break code into layers of abstraction requires using our judgement and knowledge about the problem we’re solving.

- The problems that come from having layers that are too thick are usually worse than the problems that come from having layers that are too thin. If we’re unsure, it can often be best to err on the side of making layers too thin (breaking code into distinct layers).

Chapter 3 (Thinking about other engineers)

Notes

- When writing code, it’s useful to consider the following three things:

- Things that are obvious to you are not obvious to others

- Other engineers will inadvertently try to break your code

- In time, you will forget about your own code

- Sooner or later another engineer will probably need to interact with your code, make changes to it, or make changes to something it depends on. They will not have had the benefit of all your time to understand the problem and think about how to solve it. The things that seemed completely obvious to you as you were writing the code are very likely not obvious to them.

- Your code may mean the world to you, but most other engineers at your company probably don’t know much about it, and when they do stumble upon it, they won’t necessarily have prior knowledge of why it exists or what it does. It’s highly likely that another engineer will, at some point, add or modify some code in a way that unintentionally breaks or misuses your code.

- Looking at code that you wrote a year or two ago is not much different from looking at code written by someone else. Make sure your code is understandable even to someone with little or no context, and make it hard to break. You’ll not only be doing everyone else a favor, but you’ll be doing your future self one too.

- In practice, looking at the names of things is one of the main ways in which engineers figure out how to use a new piece of code. The names of packages, classes, and functions read a bit like the table of contents of a book: they’re a convenient and quick way to find code that will solve a subproblem.

- Enforcing how your code can be used using the type system is one of the best ways to ensure that other engineers can’t misuse or misconfigure your code.

- Engineers regularly forget to update documentation when they make changes to code, so it is inevitable that some amount of documentation for code will be out of date and incorrect.

- The whole point in creating layers of abstraction is to ensure that engineers have to deal with only a few concepts at a time, and that they can use a solution to a subproblem without having to know exactly how that problem was solved. Requiring engineers to read implementation details to know how to use a piece of code obviously negates a lot of the benefits of layers of abstraction.

- Programming by contract (or design by contract) means that callers of your code are required to meet certain obligations, and in return the code being called will return a desired value, or modify some state. Nothing should be unclear or a surprise, because everything should be defined in this contract.

- Problems arise with code contracts when engineers are unaware of some or all of the terms of them. When you are writing code, it’s important to think about what the contract is and how you will ensure that anyone using your code will be aware of it and follow it.

- In real life, contracts tend to have a mixture of things that are unmistakably obvious and things that are in the small print and therefore less obvious. Everyone knows that they really should read the small print of every contract they enter, but most people don’t. Do you carefully read every sentence of every terms and conditions text thrown at you?

- When defining the contract for a piece of code there are parts that are unmistakable and parts that are more like small print:

- The unmistakable parts of the contract:

- Function and class names: A caller can’t use the code without knowing these.

- Parameter types: The code won’t even compile if the caller gets these wrong.

- Return types: A caller has to know the return type of a function to be able to use it, and the code will likely not compile if they get it wrong.

- Any checked exceptions (if the language supports them): The code won’t compile if the caller doesn’t acknowledge or handle these.

- The small print:

- Comments and documentation: Much like small print in real contracts, people really should read these (and read them fully), but in reality, they often don’t. Engineers need to be pragmatic to this fact.

- Any unchecked exceptions: If these are listed in comments then they are small print. Sometimes they won’t even be in the small print, if for example a function a few layers down throws one of these and the author of a function farther up forgot to mention it in their documentation.

- The unmistakable parts of the contract:

- Making the terms of a code contract unmistakable is much better than relying on the small print. People very often don’t read small print, and even if they do they might only skim read it and get the wrong idea. And, as discussed in the previous section, documentation has a habit of becoming out-of-date, so the small print isn’t even always correct.

- It’s better to make it impossible to do the wrong thing rather than relying on small print to try to ensure that other engineers use a piece of code correctly.

- Sometimes having small print in a piece of code’s contract is unavoidable, and in these instances it can be a good idea to add checks to ensure that the contract is adhered to. But it’s better to just avoid small print in the first place if possible. If we find ourselves adding lots of checks to a piece of code, then it might be a sign that we should instead think about how to eliminate the small print.

- A common way to enforce the conditions of a code contract is to use checks. These are additional logic that check that a code’s contract has been adhered to (such as constraints on input parameters, or setup that should have been done), and if it hasn’t, then the check throws an error (or similar) that will cause an obvious and unmissable failure. (Checks are closely related to failing fast, which is discussed in the next chapter.)

- Assertions are conceptually very similar to checks, in that they are a way to try to enforce that the coding contract is adhered to. When the code is compiled in a development mode, or when tests are run, assertions behave in much the same way as checks: a loud error or exception will be thrown if a condition is broken. The key difference between assertions and checks is that assertions are normally compiled out once the code is built for release, meaning no loud failure will happen when the code is being used in-the-wild.

Summary

- Code bases are in a constant state of flux with multiple engineers typically making constant changes

- It’s useful to think about how other engineers might break or misuse code and engineer it in a way that minimizes the chances of this or makes it impossible

- When we write code, we are invariably creating some kind of coding contract. This can contain things are are unmistakably obvious and things that are more like small print

- Small print in coding contracts is not a reliable way to ensure other engineers adhere to the contract. Making things unmistakably obvious is usually a better approach

- Enforcing a contract using the compiler is usually the most reliable approach. When this is not feasible, an alternative is to enforce a contract at runtime using checks or assertions

Chapter 4 (Errors)

Notes

- Many errors are not fatal to a piece of software, and there are sensible ways to handle them gracefully and recover. An obvious example of this is if a user provides an invalid input (such as an incorrect phone number); it would not be a great user experience if, upon entering an invalid phone number, the whole application crashed (potentially losing unsaved work). Instead, it’s better to just provide the user with a nice error message stating that the phone number is invalid, and ask them to enter a correct one.

- Examples of errors that we likely want a piece of software to recover from are:

- Network errors — if a service that we depend on is unreachable, then it might be best to just wait a few seconds and retry, or else ask the user to check their network connection if our code runs on the user’s device.

- A non-critical task error — for example, if an error occurred in a part of the software that just logs some usage statistics, then it’s probably fine to continue execution.

- Generally, most errors caused by something external to a system are things that the system as a whole should probably try to recover from gracefully. This is because they are often things that we should actively expect to happen: external systems and networks go down, files get corrupted, and users (or hackers) will provide invalid inputs.

- Sometimes errors occur that there is no sensible way for a system to recover from. Very often these occur due to a programming error where an engineer somewhere has “screwed something up.” Examples of these include the following:

- A resource that should be bundled with the code is missing

- Some code misusing another a piece of code, for example:

- Calling it with an invalid input argument

- Not pre-initializing some state that is required

- If there is no conceivable way that an error can be recovered from, then the only sensible thing that a piece of code can do is try to limit the damage and maximize the likelihood that an engineer notices and fixes the problem.

- Failing fast is about ensuring that an error is signaled as near to the real location of a problem as possible. it prevents a piece of software from ending up in an unintended and potentially dangerous state. A common example of this is when a function is called with an invalid argument. Failing fast would mean throwing an error as soon as that function is called with the invalid input, as opposed to carrying on running only to find that the invalid input causes an issue somewhere else in the code some time later.

- Failing loudly is simply ensuring that errors don’t go unnoticed. The most obvious (and violent) way to do this is to crash the program by throwing an exception (or similar). An alternative is to log an error message, although these can sometimes get ignored depending on how diligent engineers are at checking them and how much other noise there is in the logs.

- If code fails fast and fails loudly, then there is a good chance that a bug will be discovered during development or during testing (before the code is even released). Even if it’s not, then we’ll likely start seeing the error reports quite soon after release and will have the benefit of knowing exactly where the bug occurred in the code from looking at the report.

- If programming errors are caught, they should be logged and monitored in a way that ensures that engineers will notice them. This usually involves logging detailed error information so that an engineer can debug what happened, and ensuring that error rates are monitored and that engineers are alerted if the error rate gets too high.

- Sometimes it can seem tempting to just hide an error and pretend it never happened. This can make the code look a lot simpler and avoid a load of clunky error handling, but it’s almost never a good idea. Hiding errors is problematic for both errors that can be recovered from and errors that cannot be recovered from.

- The next few subsections cover some of the ways in which code can hide the fact that an error has occurred:

- Returning a default value: The problem with default values is they hide the fact that an error has occurred, meaning callers of the code will likely carry on as though everything is fine

- The null-object pattern: Examples of the null-object pattern can vary from something as simple as returning an empty list, to something as complicated as implementing a whole class

- Doing nothing: If the code in question does something (rather than returning something), then one option is to just not signal that an error has happened. This is generally bad, as callers will assume that the task that the code was meant to perform has been completed. This is very likely to create a mismatch between an engineer’s mental model of what the code does, and what it does in reality. This can cause surprises and create bugs in the software.

- With unchecked exceptions, other engineers are free to be completely oblivious to the fact a piece of code might throw one. It’s often advisable to document what unchecked exceptions a function might throw, but engineers very often forget to do this. Even if they do, this only makes the exception part of the small print in the coding contract. As we saw earlier, small print is often not a reliable way to convey a piece of code’s contract. Unchecked exceptions are therefore an implicit way of signalling an error, because there’s no guarantee that the caller will be aware that the error can happen.

- With a checked exception, the compiler forces the caller to acknowledge that it can happen by either writing code to handle it, or else declaring that the exception can be thrown in their own function signature. Using checked exceptions is therefore an explicit way of signalling an error.

- Returning a null from a function can be an effective, simple way to indicate that a certain value could not be calculated (or acquired). If the language we are using supports null safety, then the caller will be forced to be aware that the value might be null and handle it accordingly. Using a nullable return type (when we have null safety) is therefore an explicit way of signaling an error.

- A magic value (or an error code) is a value that fits into the normal return type of a function, but which has a special meaning. An engineer has to either read the documentation or the code itself to be aware that a magic value might be returned. This makes them an implicit error-signaling technique.

- Some functions just do something rather than acquiring a value and returning it. If an error can occur while doing that thing and it would be useful to signal that to the caller, then one approach is to modify the function to return a value indicating the outcome of the operation. Returning an outcome return type is an explicit way of signaling an error as long as we can enforce that callers check the return value. When writing code that executes asynchronously, it’s common to create a function that returns a promise or a future (or an equivalent concept). In many languages (but not all), a promise or a future can also convey an error state. A consumer of the promise or future is typically not forced to handle an error that may have occurred, and they would not know that they need to add error handling unless they were familiar with the small print in the code contract for the function in question. This therefore makes error signaling using a promise or a future an implicit technique.

- When an error occurs that there is no realistic prospect of a program recovering from, then it is best to fail fast and to fail loudly. Some common ways of achieving this are the following:

- Throwing an unchecked exception

- Causing the program to panic (if using a language that supports panics)

- Using a check or an assertion

- For signalling errors that a caller might want to recovered from, some engineers argue that throwing an unchecked exception (instead of using an explicit technique) can improve the code structure, because most error handling can be performed in a distinct place in a higher layer of the code. The errors bubble up to this layer and the code in between doesn’t have to be cluttered with loads of error handling logic.

- My personal opinion is that it’s best to avoid using an unchecked exception for an error that a caller might want to recover from. In my experience, the usage of unchecked exceptions very rarely gets documented fully throughout a code base, meaning it can become near impossible for an engineer using a function to have any certainty about what error scenarios may happen and which they need to handle.

- Compiler warnings can often be a sign that there is something wrong with the code, and in some scenarios this could be quite a serious bug.

Summary

- There are broadly two types of error:

- Those that a system can recover from

- Those that a system cannot recover from

- Often only the caller of a piece of code knows if an error generated by that code can be recovered from or not

- When an error does occur it’s good to fail fast and if the error can’t be recovered from to also fail loudly

- Hiding an error is often not a good idea and it’s better to signal that the error has occurred

- Error signalling techniques can be divided into two categories:

- Explicit — in the unmistakable part of the code’s contract. Callers are aware that the error can happen

- Implicit — in the small print of the code’s contract, or potentially not in the written contract at all. Callers are not necessarily aware that the error can happen

- Errors that cannot be recovered from should use implicit error signalling techniques

- For errors that can potentially be recovered from:

- Engineers don’t all agree on whether explicit or implicit techniques should be used

- My personal opinion is that explicit techniques should be used Compiler warnings can often flag that something is wrong with the code. It’s good to pay attention to them.

Chapter 5 (Make code readable)

Notes

- The essence of readability is ensuring that engineers can quickly and accurately understand what some code does. Actually achieving this often requires being empathetic and trying to imagine how things might be confusing or open to misinterpretation when seen from someone else’s point of view.

- Names are needed to uniquely identify things like classes, functions, and variables. But how we name things is also a great opportunity to make the code more readable by ensuring that things are referred to in a self-explanatory way.

- Comments should not be used as a substitute for giving things descriptive names

- If we have no choice but to include some gnarly bitwise logic or we’re having to resort to some “clever tricks” to optimize our code, then comments explaining what some low-level code does might well be useful.

- Making code self-explanatory is often preferable to using comments, because it reduces the maintenance overhead and removes the chance that comments become out-of-date.

- Comments can be very useful for explaining why something is being done, the reason that a certain piece of code exists, or the reason it does what it does.

- It’s generally good to keep an eye on the number of lines of code being added, as it can be a warning sign that the code is not reusing existing solutions or is overcomplicating something. But it’s often more important to ensure that the code is understandable, robust, and unlikely to result in buggy behavior. If it requires more lines of code to effectively do this, then that’s fine.

- Stick to a consistent coding style, a consistent coding style can make code more readable and help prevent bugs.

- Coding styles often cover many more aspects than just how to name things such as the following:

- Usage of certain language features

- How to indent code

- Package and directory structuring

- How to document code

- When a whole team or organization all follow the same coding style, it’s akin to them all speaking the same language fluently. The risk of misunderstanding each other is greatly reduced and this results in fewer bugs and less time wasted trying to understand confusing code.

- Deeply nesting code reduces readability and it’s often better to structure code in a way that minimizes the amount of nesting.

- If a function is well-named, then it should be obvious what it does, but even for a well-named function, it’s easy to have unreadable function calls if it’s not clear what the arguments are for or what they do.

- Having an unexplained value in the code can cause confusion and bugs. It’s important to ensure that what the value means is obvious to other engineers. One solution is to store them in a well-named variable.

- If the contents of an anonymous function are not self-explanatory then the code is likely not readable and it’s preferred to use a named-functions instead.

- If an anonymous function starts approaching anything more than two or three lines long, then it’s quite likely that the code would be more readable if the anonymous function is broken apart and placed into one or more named functions.

- Using a language feature when it improves code is a good idea. But, if the improvement is small or there’s a chance others may not be familiar with the feature, it may still be best to avoid using it.

Summary

- If code is not readable and easy to understand then it can lead to problems such as the following:

- Other engineers wasting time trying to decipher it

- Misunderstandings that lead to bugs being introduced

- Code being broken when other engineers need to modify it

- Making code more readable can sometimes lead to it becoming more verbose and taking up more lines. This is often a worthwhile trade-off

- Making code readable often requires being empathetic and imagining ways in which others might find something confusing

- Real-life scenarios are varied and usually present their own set of challenges. Writing readable code nearly always requires an element of applying common sense and using your judgement.

Chapter 6 (Avoid surprises)

Notes

- If we write code that can cause a surprise, we are relying on someone else’s diligence to not fall into the trap we have set. At some point this will not happen and someone will fall into it.

- Avoid returning magic values, returning a magic value carries a risk of causing a surprise, so it’s often best to not use them.

- Returning a magic value is sometimes a conscious decision made by an engineer, but it can also sometimes happen by accident. Regardless of the reason, magic values can easily cause surprises so it’s good to be vigilant for scenarios where they can occur. Returning null, optional, or using an error signalling technique are simple and effective alternatives.

- The null-object pattern is an alternative to returning null (or an empty optional) when a value can’t be obtained. The idea is that instead of returning null a valid value is returned that will cause any downstream logic to behave in an innocuous way. The simplest forms of this are returning an empty string or an empty list.

- When a side-effect is expected and what a caller to a piece of code wants, then it is fine, but when a side-effect is unexpected, it can cause a surprise and lead to bugs.

- Not causing a side-effect in the first place is the best way to avoid a surprise, but this is not always practical. So when a side-effect is unavoidable, naming things appropriately can be a very effective way to make it obvious.

- Modifying (or mutating) an input parameter is an example of a side-effect, because the function is affecting something outside of itself. It’s conventional for functions to take inputs via parameters and provide results via return values. So to most engineers this is an unexpected side-effect and is likely to cause a surprise.

- If a set of values contained within an input parameter really need to be mutated, then it’s often best to copy them into a new data structure before performing any mutations. This prevents the original object from being changed.

- A parameter is critical to a function if the function can’t do what it says it does without that parameter. If we have such a parameter, then it can often be safer to just make it required, so that it’s impossible to call the function if the value is not available.

- Testing is extremely important. No amount of code structuring or worrying about code contracts will ever replace the need for high-quality and thorough testing. But in my experience the reverse is also true; testing alone does not make up for unintuitive or surprising code.

Summary

- The code we write will often be depended on by code that other engineers write.

- If other engineers misinterpret what our code does, or fail to spot special scenarios they need to handle, then it’s likely that code built on top of ours will be buggy.

- One of the best ways to avoid causing surprises for callers of a piece of code is to ensure that important details are in the unmistakably obvious part of the code’s contract.

- Another source of surprises can occur if we make brittle assumptions about code that we depend on.

- An example of this is failing to anticipate new values being added to an enum.

- It’s important to ensure that either our code stops compiling or a test fails if code that we depend on breaks one of our assumptions.

- Testing alone does not make up for code that does surprising things: if another engineer misinterprets our code, then they may also misinterpret what scenarios they need to test.

Chapter 7 (Make code hard to misuse)

Notes

- It’s not always possible or appropriate to make things immutable. There are inevitably some parts of our code that have to keep track of changing state, and these will obviously require some kinds of mutable data structures to do this. But, as was just explained, having mutable objects can increase the complexity of the code and lead to problems, so it can often be a good idea to take the default stance that things should be as immutable as possible and make things mutable only where it’s necessary.

- One of the most common ways a class is made mutable is by providing setter functions.

- We can make a class immutable (and prevent it being misused) by ensuring that all the values are provided at construction time and that they cannot be changed after this.

- If some values are optional or if mutated versions of the class need to be created, it can often be necessary to implement the class in a more versatile way. Two design patterns that can often be useful for this are the The builder pattern, The copy-on-write pattern

- Defensively copying things can be quite effective at making a class deeply immutable, but it has some obvious drawbacks:

- Copying things can be expensive.

- It often doesn’t protect against changes from within the class.

- Using immutable data structures is one of the best ways to ensure that classes are deeply immutable. They avoid the downsides of defensively copying things and ensure that even code within the class can’t inadvertently cause mutations.

- Just because something can be represented by a type like an integer or a list doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s a good way to represent that thing. The lack of descriptiveness and the amount of permissiveness can make code too easy to misuse. Ex: using

List<List<Double>>to store locations where the inner list should contain exactly two values, lat and long. - Using a

List<Double>is a kind of hacky way to represent a map location and can be easily misused. - Doing one thing in a slightly hacky way can often force more stuff to be done in a hacky way.

Using

Pair<Double, Double>instead ofList<Double>solves the problem of accidentally providing too few or too many values as the pair has to contain exactly two values. But it does not solve the other problems:- The type

List<Pair<Double, Double>>still does very little to explain itself. - It’s still easy for an engineer to get confused about which way around the latitude and longitude should be.

- The type

- For representing a list of locations, a simple way to make the code less easy to misuse and misinterpret is to define a dedicated class for representing a latitude and longitude.

List<LatLong> locations - It can seem like a lot of effort or overkill to define a new class (or struct) to represent something, but it’s usually less effort than it might seem and will save engineers a lot of head scratching and potential bugs further down the line.

- Using very general, off-the-shelf data types can sometimes seem like a quick and easy way to represent something. But when we need to represent a specific thing it can often be better to put in a small amount of extra effort to define a dedicated type for it. In the mid- to long-run, this usually saves time because the code becomes a lot more self-explanatory and hard to misuse.

- A common way of representing time is to use an integer (or a long integer), which represents a number of seconds (or milliseconds). This is often used for representing both instants in time as well as amounts of time:

- An instant in time is often represented as a number of seconds (ignoring leap seconds) since the unix epoch (00:00:00 UTC on 1 January 1970).

- An amount of time is often represented as a number of seconds (or milliseconds).

- An integer is a very general type and can thus make code easy to misuse when used to represent time like this.

- An integer type does absolutely nothing to indicate which units (seconds, milliseconds) the value is in, or whether it’s an instant in time or an amount of time. We can indicate that using a function name, parameter name, or documentation, but this can often still leave it relatively easy to misuse some code.

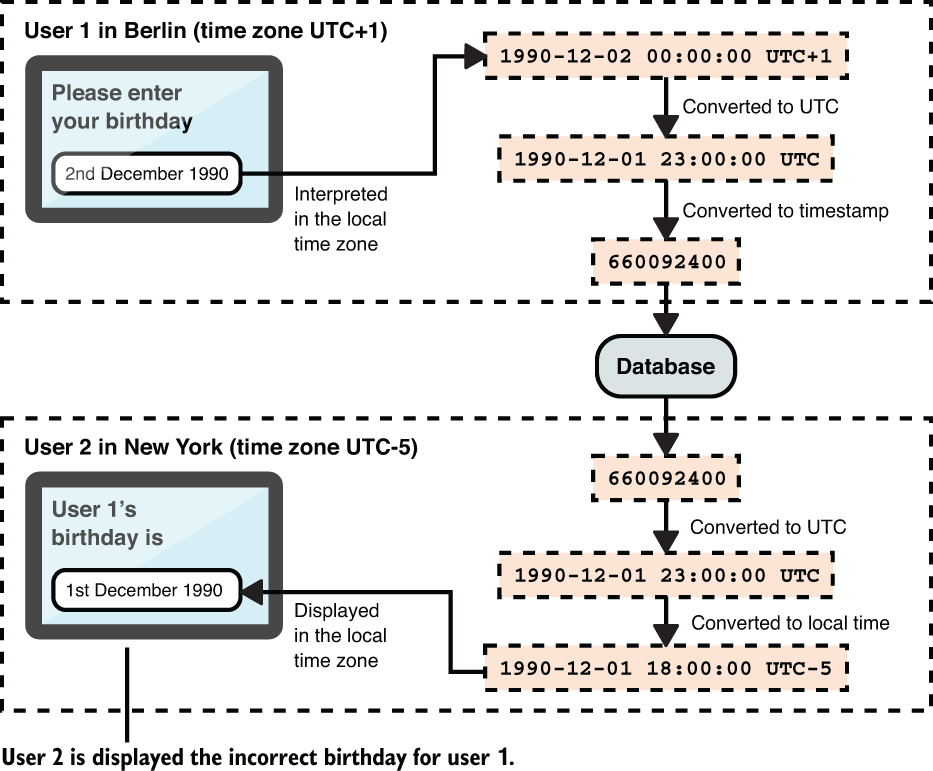

- If a user enters a date (like their birthday) and this is interpreted as being a date and time within a local time zone, this can lead to a different date being displayed when a user in a different time zone accesses the information.

- A problem similar to that described in the previoud figure can also happen in purely server-side logic if servers are running in different locations and have their systems set to different time zones. For example a server in California might save a date value that a different server in Europe ends up processing.

- Time-based concepts like instants in time, amounts of time, and dates can be tricky things to work with at the best of times. But we make our own lives and other engineers’ lives even harder when we try to represent them using a very general type like an integer. Integers convey very little information about what they mean or represent, and this can make them very easy to misuse.

- Solution: Use appropriate data structures for time, either the programming language’s built-in libraries for handling time or third-party, opensource libraries.

- The java.time, Noda Time, and js-joda libraries all provide a class called Instant (for representing an instant in time) and a separate class called Duration (for representing an amount of time).

- Using one of these means that the type of a function parameter dictates whether it represents an instant in time or an amount of time.

- In the example of representing a birthday we don’t actually care what the time zone is. But if we want to represent a birthday by linking it to an exact instant in time (using a timestamp), then we are forced to think carefully about time zones. Luckily, libraries for handling time often provide a way to represent a date (and time) without having to link it to an exact instant in time like this. The java.time, Noda Time, and js-joda libraries all provide a class called

LocalDateTime, which achieves exactly this. - Have single sources of truth for data

- Primary data: Things that need to be supplied to the code.

- Derived data: Things that the code can calculate based on the primary data.

- Primary data usually provides the source of truth for a program. For example, in case of a bank account, the values for the credit and debit fully describe the state of an account, they can be used to derive the balance (credit minus debit), storing the balance (second sources of truth) might lead to an invalid state.

- When the logic performed by two different pieces of code need to match, we shouldn’t leave it to chance that they do. Engineers working on one part of the codebase may not be aware of an assumption made by some code in another part of the codebase. We can make code a lot more robust by ensuring that important pieces of logic have a single source of truth. This almost entirely eliminates the risk of bugs caused by different pieces of code getting out of sync with one another.

Summary

- If code is easy to misuse, then there is a high chance that at some point it will be misused. This can lead to bugs.

- Some common ways in which code can be misused are the following:

- Callers providing invalid inputs

- Side effects from other pieces code

- Callers not calling functions at the correct times or in the correct order

- A related piece of code being modified in a way that breaks an assumption

- It’s often possible to design and structure code in a way that makes it hard or impossible to misuse. This can greatly reduce the chance of bugs and save engineers a lot of time in the mid- to long-term.

Chapter 8 (Make code modular)

Notes

- One of the main aims of modularity is to create code that can be easily adapted and reconfigured, without having to know exactly how it will need to be adapted or reconfigured. A key goal in achieving this is that different pieces of functionality (or requirements) should map to distinct parts of the codebase.

- Dependency injection can be an excellent way to make code modular and ensure that it can be adapted to different use cases. Whenever we’re dealing with subproblems that might have alternative solutions, this can be particularly useful.

- We can make a class a lot more modular and versatile if we allow it to be injected by different implementations of its dependencies. We can achieve this by injecting these dependencies by providing them via a parameter in the constructor.

- When writing code, it can often be beneficial to consciously consider that we might want to use dependency injection. There are ways of writing code that make it near impossible to use dependency injection, so if we know we might want to inject a dependency, it’s best to avoid these.

- Making your class use the implementation of its dependency classes via static functions makes it harder to refactor the code to use dependency injection.

- Depending on concrete implementation classes often limits adaptability compared to depending on an interface. Depending on the more abstract interface will usually achieve cleaner layers of abstraction and better modularity.

- If we’re depending on a class that implements an interface and that interface captures the functionality that we need, then it’s usually better to depend on that interface rather than directly on the class, as the dependency class can be replaced with any other class that implements the same interface.

- Inheritance is a powerful tool, but it can also have several drawbacks and be quite unforgiving in terms of the problems it causes, so it’s usually worth thinking carefully before writing code where one class inherits from another.

- In many scenarios, an alternative to using inheritance is to use composition. This means that we compose one class out of another by passing an instance of it rather than extending it.

- When using inheritance, a subclass inherits and exposes any functionality from the superclass, this may result in a very strange public API for the subclass. If we use composition instead, then none of the functionality of the class being composed is exposed, unless functions are explicitly exposed using forwarding (public functions calling functions from the class being composed) or delegation.

- When using inheritance, in case of new requirements that are not met by the superclass, we will have to create another class that extends another superclass that meets these requirements. But if we use composition we can just inject the new class providing the needed functionality.

- Inheritance can make sense when two classes have a genuine is-a relationship: a Ford Mustang is a car, so we might make a FordMustang class extend a Car class.

- But it’s worth being aware that even when there is a genuine is-a relationship, inheritance can still be problematic. Some things to watch out for are as follows:

- The fragile base class problem: If a subclass inherits from a superclass and the superclass is later modified, this can sometimes break the subclass.

- The diamond problem: Some languages support multiple inheritance. This can lead to issues if multiple superclasses provide versions of the same function, because it can be ambiguous as to which superclass the function should be inherited from.

- Problematic hierarchies: Many languages support only single inheritance. This can lead to problems when a class logically belongs in more than one hierarchy.

- If a single concept is completely contained within a single class. Any change in requirements related to that concept will require modifying only that single class.

- One of the key aims of making code modular is that a change in requirements should result in changes only to those parts of the code that directly relate to that requirement. Classes often need some amount of knowledge of one another, but it’s often worth minimizing this as much as possible. This can help keep code modular and can greatly improve adaptability and maintainability.

- When a single concept gets spread across multiple classes. Any change in requirements related to that concept will require modifying multiple classes. And if an engineer forgets to modify one of these classes, then this might result in a bug. A common way this can happen is when a class cares too much about the details of another class.

- The Law of Demetera (sometimes abbreviated LoD) is a software engineering principle that states that one object should make as few assumptions as possible about the content or structure of other objects. In particular, the principle advocates that an object should interact only with other objects that it’s immediately related to.

- Group related data into objects or classes, it makes sense to encapsulate related data together into a single object that can then be passed around.

- When different pieces of data are inescapably related to one another, and there’s no practical scenario in which someone would want some of the pieces of data without wanting the others, then it usually makes sense to encapsulate them together.

- In order to have clean layers of abstraction, it’s necessary to ensure that layers don’t leak implementation details. If implementation details are leaked, this can reveal things about lower layers in the code and can make it very hard to modify or reconfigure things in the future.

- One of the most common ways code can leak an implementation detail is by returning a type that is tightly coupled to that detail.

- Another way a code can leak an implementation detail is by throwing an error that is tightly coupled to that detail.

- If we know for sure that an error is not one any caller would ever want to recover from, then leaking implementation details is not a massive issue, as higher layers probably won’t try to handle that specific error anyway. But whenever we have an error that a caller might want to recover from, it’s often important to ensure that the type of the error is appropriate to the layer of abstraction.

Summary

- Modular code is often easier to adapt to changing requirements.

- One of the key aims of modularity is that a change in a requirement should only affect parts of the code directly related to that requirement.

- Making code modular is highly related to creating clean layers of abstraction.

- The following techniques can be used to make code modular:

- Using dependency injection

- Depending on interfaces instead of concrete classes

- Using interfaces and composition instead of class inheritance

- Making classes care about themselves

- Encapsulating related data together

- Ensuring that return types and exceptions don’t leak implementation details

Chapter 9 (Make code reusable and generalizable)

Notes

- Making assumptions can sometimes result in code that is simpler, more efficient, or both. But assumptions also tend to result in code that is more fragile and less versatile, which can make it less safe to reuse. It’s incredibly hard to keep track of exactly which assumptions have been made in which parts of the code, so they can easily turn into nasty traps that other engineers will inadvertently fall into.

- Optimizing code generally has a cost associated with it: it often takes more time and effort to implement an optimized solution, and the resulting code is often less readable, harder to maintain, and potentially less robust (if assumptions are introduced)

- In most scenarios, it’s better to concentrate on making code readable, maintainable, and robust rather than chasing marginal gains in performance. If a piece of code ends up being run many times and it would be beneficial to optimize it, this can be done later at the point this becomes apparent.

- When writing code, we’re often very alert to things like the performance costs of running a line of code more times than necessary. But it’s important to remember that assumptions also carry an associated cost in terms of fragility. If making a particular assumption results in a big performance gain or enormously simplified code, then it might well be a worthwhile one to make. But if the gains are marginal, then the costs associated with baking an assumption into the code might well outweigh the benefits.

- Sometimes making an assumption is necessary, or simplifies the code to such an extent that the benefits outweigh the costs. When we do decide to make an assumption in the code, we should enforce it. There are generally two approaches we can take to achieve this:

- Make the assumption “impossible to break” - If we can write the code in such a way that it won’t compile if an assumption is broken.

- Use an error-signaling technique - If it’s not feasible to make the assumption impossible to break, then we can write code to detect it being broken and use an error-signaling technique to fail fast.

- To sum up, assumptions tend to have an associated cost in terms of increased fragility. When the costs of a given assumption outweigh the benefits, it’s probably best to avoid making it. If an assumption is necessary, then we should do our best to ensure that other engineers don’t get caught by it; we can achieve this by enforcing the assumption.

- Global state is one of the most well-known and well-documented coding pitfalls. It can be very tempting to use it because it can seem like a quick and easy way to share information between different parts of a program. But using global state can make code reuse completely unsafe. The fact that global state is used might not be apparent to another engineer, so if they do try to reuse the code, this might result in weird behavior and bugs.

- If we need to share state between different parts of a program, rather than using global state. it’s usually safer to do this in a more controlled way using dependency injection.

- By bundling a default return value into the lower level code, we’ve made an assumption about every potential layer of code above.

- Provide defaults in higher level code. Shifting the decision about what default value to use to the caller tends to make code more reusable.

- Returning a default value from low-level code makes an assumption about all of the layers of code above that use the value and can thus limit code reuse and adaptability. It can often be better to simply return null and implement default values at a higher level, where assumptions are more likely to hold.

- In general, making functions take only what they need results in code that is more reusable and easier to understand. It’s still good to apply your judgment, though. If we have a class that encapsulates 10 things together and a function that needs 8 of them, then it might still make sense to pass the entire encapsulating object into the function.

- If we’re writing some code that references another class, but we don’t particularly care what that other class is, then it’s often a sign that we should consider using generics. Doing this is often very little extra work but makes our code considerably more generalizable.

- When the solution to a subproblem could easily apply to any data type, it’s often very little effort to use generics instead of depending on a specific type. This can be an easy win in terms of making code more generalizable and reusable.

Summary

- The same subproblems often crop up again and again, so making code reusable can save your future self and your teammates considerable time and effort.

- Try to identify fundamental subproblems and structure the code in a way that will allow others to reuse the solutions to specific subproblems even if they’re solving a different high-level problem.

- Creating clean layers of abstraction and making code modular often result in code that is a lot easier and safer to reuse and generalize.

- Making an assumption often has a cost in terms of making the code more fragile and less reusable.

- Make sure the benefits of an assumption outweigh the costs.

- If an assumption does need to be made, then make sure it’s in an appropriate layer of the code and enforce it if possible.

- Using global state often makes a particularly costly assumption that results in code that is completely unsafe to reuse. In most scenarios, global state is best avoided.

Chapter 10 (Unit testing principles)

Notes

- Unit testing is concerned with testing distinct units of code in a relatively isolated manner. What exactly we mean by a unit of code can vary, but it often refers to a specific class, function, or file of code.

- At a practical level, a test case is usually just a function, and for anything other than the simplest of test cases, it’s common to divide the code within each of them into three distinct sections as follows:

- Arrange: It’s often necessary to perform some setup before we can invoke the specific behavior we want to test. This could involve defining some test values, setting up some dependencies, or constructing a correctly configured instance of the code under test (if it’s a class). This is often placed in a distinct block of code at the start of the test case.

- Act: This refers to the lines of code that actually invoke the behavior that is being tested. This typically involves calling one or more of the functions provided by the code under test.

- Assert: Once the behavior being tested has been invoked, the test needs to check that the correct things actually happened. This typically involves checking that a return value is equal to an expected value or that some resultant state is as expected.

- Test runner: As the name suggests, a test runner is a tool that actually runs the tests. Given a file of test code (or several files of test code), it will run each test case and output details of which pass and which fail.

- five key features that a good unit test should exhibit:

- Accurately detects breakages: If the code is broken, a test should fail. And a test should only fail if the code is indeed broken (we don’t want false alarms).

- Agnostic to implementation details: Changes in implementation details should ideally not result in changes to tests.

- Well-explained failures: If the code is broken, the test failure should provide a clear explanation of the problem.

- Understandable test code: Other engineers need to be able to understand what exactly a test is testing and how it is doing it.

- Easy and quick to run: Engineers usually need to run unit tests quite often during their everyday work. A slow or difficult-to-run unit test will waste a lot of engineering time.

- If the code under test is broken in any way, it should either not compile or a test should fail.

- A piece of functionality being broken by a code change (or some other event), is known as a regression. Running tests with the aim of detecting any such regressions is known as regression testing.

- A test that sometimes passes and sometimes fails despite the code under test being fine is referred to as flaky. This is usually a result of indeterministic behavior in the test, such as randomness, timing-based race conditions, or depending on an external system. Ensuring that tests fail when something is broken, and only when something is broken, is incredibly important.

- Don’t mix functional changes and refactorings. It’s usually better to do the refactoring and then make the functional change separately. This makes it a lot easier to isolate the cause of any potential problems.

- By making tests agnostic to implementation details, we can ensure that tests failing after refactoring is a reliable signal that we did a mistake while refactoring.

- To ensure that tests clearly and precisely explain what is broken, it’s necessary to think about what kind of failure message the test will produce when something is wrong and whether this will be useful to another engineer.

- One of the best ways to ensure that test failures are well explained is to test one thing at a time and use descriptive names for each test case. This often results in many small test cases that each lock in one specific behavior rather than one large test case that tries to test everything in one go. When a test starts failing, it’s quite easy to see exactly which behaviors have been broken by checking the names of the test cases that fail.

- A test failing indicates that the code now behaves in a different way, either because it got broken or because an engineer deliberately modified its functionality.

- Engineers will need to update the tests to reflect the new functionality, so test code should be easy to understand and reason about.

- For an engineer to have confidence that their change is affecting only the desired behavior, they need to be able to know which parts of the tests they’re affecting and whether they need updating. Two common ways this can go wrong are testing too many things at once and using too much shared test setup. These can lead to tests that are very hard to understand and reason about. This makes future modifications to the code under test much less safe, because engineers will struggle to understand whether specific changes they’re making are safe.

- Another reason to strive for making test code understandable is that some engineers like to use the tests as a kind of instruction manual for the code. If they’re wondering how to use a particular piece of code or what functionality it provides, then reading through the unit tests can be a good way to find this out. If the tests are difficult to understand, they won’t make a very useful instruction manual.

- If the unit tests take an hour to run, this will slow every engineer down, because submitting a code change will take a minimum of an hour regardless of how small or trivial it is. In addition to being run before submitting changes to the codebase, engineers often run unit tests numerous times while developing the code, so this is another way that slow unit tests slow engineers down.

- Another reason to keep tests fast and easy to run is to maximize the chance that engineers actually test stuff. When tests are slow, testing becomes painful, and if testing is painful, engineers tend to do less of it.

- By focusing on testing only the public API, it forces us to concentrate on the behaviors that users of a piece of code ultimately care about rather than details that are just a means to an end. This helps ensure that we test the things that actually matter, and in the process also tends to .

- By concentrating on testing the public API, we’re forced to write tests that lock in the behaviors that callers actually care about, rather than implementation details that might be replaced or refactored in the future. We might, therefore, write a series of test cases that check that the expected value is returned for given inputs.

- Let’s consider a function takes an integer and outputs its double. If we felt the temptation to write a test that checked that the function calls

Math.pow(), then the principle of “test using only the public API” would guide us away from this. This prevents us from coupling our tests to implementation details and ensures that we concentrate on testing the things that callers actually care about. - Tests should aim to test things using the public API whenever possible. But it can often be necessary for tests to interact with dependencies that are not part of the public API in order to perform setup and to verify desired side effects.

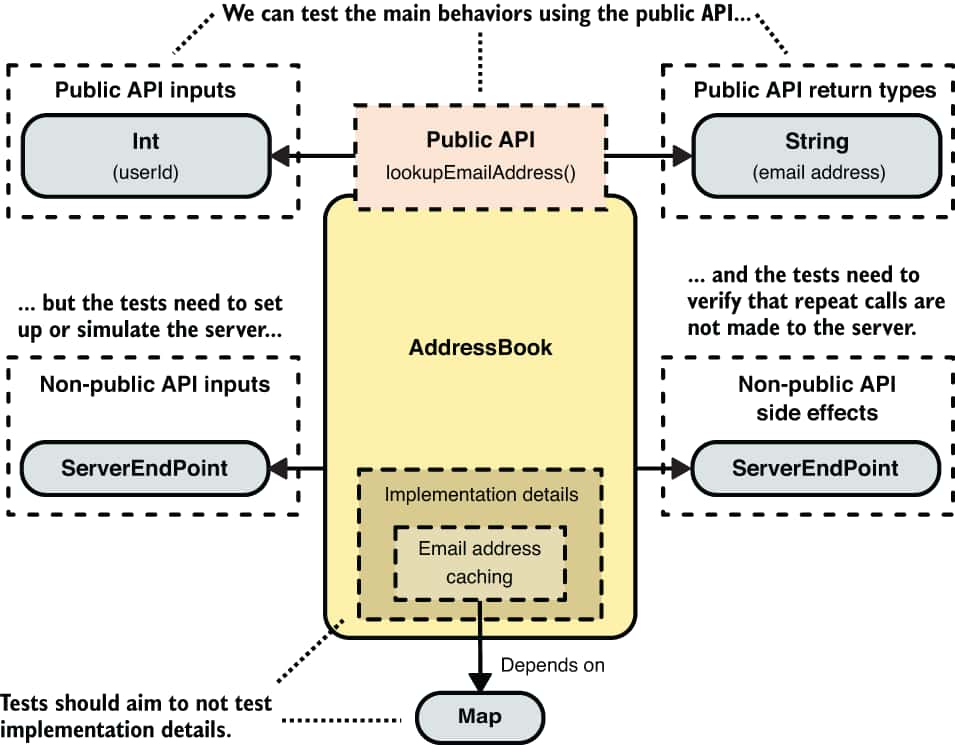

- Consider the following code. The

AddressBookclass allows a caller to look up the email address for a user. It achieves this by fetching the email address from a server. It also caches any previously fetched email addresses to prevent overloading the server with repeat requests. As far as anyone using this class is concerned, they calllookupEmailAddress()with a user ID and get back an email address (or null if there is no email address), so it would be reasonable to say that thelookupEmailAddress()function is the public API of this class. This means that the fact that it depends on theServerEndPointclass and caches email addresses are both implementation details as far as users of the class are concerned.

class AddressBook {

private final ServerEndPoint server;

private final Map<Int, String> emailAddressCache;

...

String? lookupEmailAddress(Int userId) {

String? cachedEmail = emailAddressCache.get(userId);

if (cachedEmail != null) {

return cachedEmail;

}

return fetchAndCacheEmailAddress(userId);

}

private String? fetchAndCacheEmailAddress(Int userId) {

String? fetchedEmail = server.fetchEmailAddress(userId);

if (fetchedEmail != null) {

emailAddressCache.put(userId, fetchedEmail);

}

return fetchedEmail;

}

}

- The public API reflects the most important behavior of the class: looking up an email address given a user ID. But we can’t test this unless we set up (or simulate) a

ServerEndPoint. In addition to this, another important behavior is that repeated calls tolookupEmailAddress()with the same user ID don’t result in repeated calls to the server. This is not part of the public API (as we defined it), but it’s still an important behavior because we don’t want our server to get overloaded, and we should therefore test it. Note that the thing we actually care about (and should test) is that repeat requests are not sent to the server. The fact that the class achieves this using a cache is just a means to this end and is, therefore, an implementation detail even to tests. The following figure illustrates the dependencies of theAddressBookclass and how tests might need to interact with them.

- “Test using only the public API” and “don’t test implementation details” are both excellent pieces of advice, but we need to appreciate that they are guiding principles and that their definition can be subjective and context specific. What ultimately matters is that we properly test all the important behaviors of the code, and there may be occasions where we can’t do this using only what we consider the public API. But we should still stay alert to the desire to keep tests agnostic to implementation details as much as possible, so we should stray away from the public API only when there really is no alternative.

- An alternative to using a real dependency is to use a test double. A test double is an object that simulates a dependency, but in a way that makes it more suitable to use in tests.

- Three common reasons why we might want to use a test double:

- Simplifying a test: Some dependencies are tricky and painful to use in tests.

- Protecting the outside world from the test: Some dependencies have real-world side effects.

- Protecting the test from the outside world: The outside world can be indeterministic.

- Setting up a test double can also sometimes be more complicated than using a real dependency, so the arguments for and against using a test double to simplify a test need to be considered on a case-by-case basis.

- A mock simulates a class or interface by providing no functionality other than just recording what calls are made to member functions. In doing so, it also records what values are supplied for arguments when a function is called.

- A mock can be used in a test to verify that the code under test makes certain calls to functions provided by a dependency. A mock is, therefore, most useful for simulating a dependency that the code under test causes a side effect in.

- A stub simulates a function by returning predefined values whenever the function is called. This allows tests to simulate dependencies by stubbing certain member functions that the code under test will call and use the return values from.

- Stubs are useful for simulating dependencies that code takes an input from.

- Although there is a clear difference between mocks and stubs, in casual conversation, many engineers just use the word mock to refer to both.

- Two of the main downsides of Mocks and Stubs are as follows:

- They can lead to tests that are unrealistic if a mock or a stub is configured to behave in a way that is different to the real dependency.

- They can cause tests to become tightly coupled to implementation details, which can make refactoring difficult.

- One of the major drawbacks of using a mock is that the engineer writing the test has to decide how the mock will behave, and if they made a mistake in understanding how the real dependency works, then they will likely make the same mistake when they configure the mock.This is one of the major drawbacks of using a mock

- This same problem can apply to the usage of stubs. Using a stub will test that our code behaves how we want it to when a dependency returns a certain value. But it tests nothing about whether that is actually a realistic value for that dependency to return.

- A fake is an alternative implementation of a class (or interface) that can safely be used in tests. A fake should accurately simulate the public API of the real dependency, but the implementation is typically simplified. This can often be achieved by storing state in a member variable within the fake instead of communicating with an external system.

- The whole point in a fake is that its code contract is identical to the real dependency, so if the real class (or interface) doesn’t accept a certain input, then the fake shouldn’t either. This typically means that a fake should be maintained by the same team that maintains the code for the real dependency, because if the code contract of the real dependency ever changes, then the code contract of the fake will also need to be updated.

- Broadly speaking there are two schools of thought around the usage of mocks (and stubs) in unit tests:

- Mockist: Proponents argue that engineers should avoid using real dependencies in tests and instead use mocks. Avoiding the usage of real dependencies and using lots of mocks often also implies the need to use stubs for any parts of dependencies that provide inputs, so using a mockist approach often also involves stubbing as well as mocking.

- Classicist: Proponents argue that the usage of mocks and stubs should be kept to a minimum and that engineers should prefer using real dependencies in tests. When it’s not feasible to use a real dependency, then using a fake is the next preference. Mocks and stubs should only be used as a last resort when it’s not feasible to use either the real dependency or a fake.

Summary

- Pretty much every piece of “real code” submitted to the codebase should have an accompanying unit test.

- Every behavior that the “real code” exhibits should have an accompanying test case that exercises it and checks the result. For anything other than the simplest of test cases, it’s common to divide the code within each of them into three distinct sections: arrange, act, and assert.

- The key features of a good unit test are as follows:

- Accurately detects breakages

- Is agnostic to implementation details

- Has well-explained failures

- Has understandable test code

- Is easy and quick to run

- Test doubles can be used in a unit test when it’s infeasible or impractical to use a real dependency. Some examples of test doubles are the following:

- Mocks

- Stubs

- Fakes

- Mocks and stubs can result in tests that are unrealistic and that are tightly coupled to implementation details

- There are different schools of thought on the usage of mocks and stubs. My opinion is that real dependencies should be used in tests where possible. Failing that, a fake is the next best option, while mocks and stubs should be used only as a last resort.

Chapter 11 (Unit testing practices)

Notes

- It’s quite often the case that even a single function can exhibit many different behaviors depending on the values it’s called with or the state that the system is in. Writing just one test case per function rarely results in an adequate amount of testing. Instead of concentrating on functions, it’s usually more effective to identify all the behaviors that ultimately matter and ensure that there is a test case for each of them.

- The exercise of thinking up behaviors to test is a great way to spot potential problems with the code.

- A good way to measure whether a piece of code is tested properly is to think about how someone could theoretically break the code and still have the tests pass. Some good questions to ask while looking over the code are as follows. If the answer to any of them is yes, then this suggests that not all the behaviors are being tested:

- Are there any lines of code that could be deleted and still result in the code compiling and the tests passing?

- Could the polarity of any if-statements (or equivalent) be reversed and still result in the tests passing?

- Could the values of any constants or hard-coded values be changed and still result in the tests passing?

- If there is an important behavior that the code exhibits, then there should be a test case to test that behavior, so any change in functionality to the code should result in at least one test case failing. If it doesn’t, then not all the behaviors are being tested.

- How a piece of code handles and signals different error scenarios are important behaviors that we (and callers of our code) care about. They should therefore be tested.

- Private functions are implementation details, and they’re not something that code outside the class should be aware of or ever make direct use of. Sometimes it can seem tempting to make some of these private functions visible to the test code so that they can be directly tested. But this is often not a good idea, as it can result in tests that are tightly coupled to implementation details and that don’t test the things we ultimately care about.

- When we find ourselves making a private function visible so that we can test the code, it’s usually a warning sign that we’re not testing the behaviors that we actually care about. It’s nearly always better to test the code using public API. If this is infeasible, then it’s often a sign that the class (or unit of code) is too big and that we should think about splitting it up into smaller classes (or units) that each solve a single subproblem. Then each can be tested separately.

- Test each behavior in its own test case. Testing all the behaviors in one go leads to non understandable test code. And makes it harder to identify which behavior has changed if the test failed.

- Despite the benefits of testing one thing at a time, writing a separate test case function for each behavior can sometimes lead to a lot of code duplication. Some testing frameworks provide functionality for writing parameterized tests; this allows us to write a test case function once but then run it multiple times with different sets of values in order to test different scenarios.

- Sharing mutable state between test cases is less than ideal. If it can be avoided this is usually preferable. If it can’t be avoided, we should ensure that the state is reset between each test case. This ensures that test cases don’t have adverse effects on one another.

- When a piece of configuration directly matters to the outcome of a test case, it’s usually best to keep it self-contained within that test case. This defends against future changes inadvertently ruining the tests.

- Some pieces of configuration are necessary but don’t directly affect the outcome of test cases. In scenarios like this, using shared configuration is okay.

- Shared test setup can be a bit of a double-edged sword. It can be very useful for preventing code repetition or repeatedly performing expensive setup, but it also runs the risk of making tests ineffective and hard to reason about. It’s worth thinking carefully to ensure that it’s used in an appropriate way.

- In addition to ensuring that a test fails when the code is broken, it’s important to think about how a test will fail. Using an appropriate assertion matcher can often make the difference between a well-explained test failure and a poorly explained one that will leave other engineers scratching their heads.

- Testability is heavily related to modularity. When different pieces of code are loosely coupled and reconfigurable, it tends to be much easier to test them.

- Hard-coded dependencies can make code impossible to test.

- Dependency injection considerably increase the testability of code as it allows you to construct the code under test with test doubles.

Summary

- Concentrating on testing each function can easily lead to insufficient testing. It’s usually more effective to identify all important behaviors and write a test case for each.

- Test the behaviors of the code that ultimately matter. Testing private functions is nearly always an indication that we’re not testing the things that ultimately matter.

- Testing one thing at a time results in tests that are easier to understand, as well as better explained test failures.

- Shared test setup can be a double-edged sword. It can avoid the repetition of code or expensive setup, but it can also lead to ineffective or flaky tests when used inappropriately.

- The use of dependency injection can considerably increase the testability of code. Unit testing is the level of testing that engineers tend to deal with most often, but it’s by no means the only one. Writing and maintaining software to a high standard often requires the use of multiple testing techniques.